Father Leonard Feeney and the

Saint Benedict Center Revisited

Here is part one of a two-part series reevaluating a highly re-spected Irish Catholic dissident—respected, that is, until he was “canceled” by the Catholic Church and mainstream academia.

By Antonius J. Patrick

Published in The Barnes Review January/February 2024 BARNESREVIEW.ORG 1-877-773-9077 Toll Free

More than 70 years ago, on February 13, 1953, the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office issued the decree which excommunicated the Rev. Father Leonard Feeney, S.J., (1897-1978). The Holy Office’s decision was the culmination of what had become a heated and sometimes violent controversy which began in earnest in 1949 over the issue of extra ecclesiam nulla salus (outside the Church there is no salvation).

A number of learned Catholics believe that the excommunication was invalid as was Feeney’s silencing by the Boston Archdiocese and his expulsion from the Jesuit order since none of them followed proper canonical procedures.

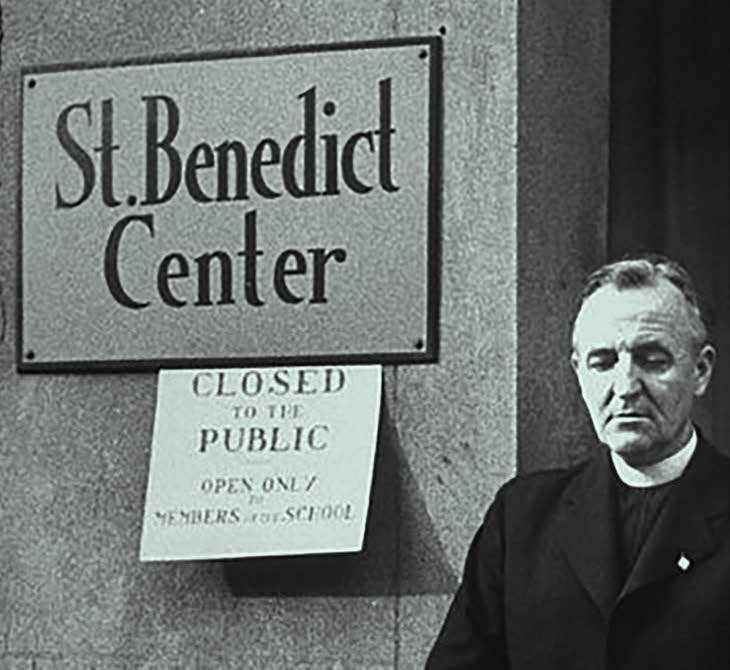

In his publications—including his newsletter The Point, which ran throughout the 1950s—lectures, sermons, and his association with the St. Benedict Center in Boston, Feeney courageously spoke out about the growing power of the Jews in America and the Church’s ecumenical and accommodating approach to them long before Vatican II.

Besides discussing Jews, Feeney was an ardent anti-Communist, but, unlike Cold War warriors such as William Buckley, he questioned, as did other members of the St. Benedict Center, America’s alliance with Josef Stalin during World War II. The priest also spoke out against America’s decision to incinerate Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear weapons, which he considered a war crime. Furthermore, he warned about cultural Marxism, which was making inroads in American higher education, most notably at Harvard University, but also in Catholic schools as well.

As history unfolds, it has become clearer that the “silencing” of Feeney by the Church and his unjust expulsion from the Jesuit order of which he was one of its most well-known members at the time, paved the way, in part, for the revolutionary changes that took place at the Vatican II Council and in its aftermath.

FR. FEENEY’S EARLY YEARS

Feeney was born in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1897 to Irish parents, although his father had Spanish lineage. He had two brothers who became priests and one sister. A precocious young man, he entered the Jesuit order as a novice at 17 and became a priest in 1928. He was sent to England for graduate work at Oxford and, at the time, began to publish both in prose and poetry.

“So successful did he assimilate all that he was taught,” writes Catholic journalist Gary Potter, “the day would come when he was hailed by a Jesuit provincial as ‘the greatest theologian we have in the United States by far’.” (1)

In the coming years of controversy, instead of praise, Feeney’s theological acumen would be severely questioned by the Jesuits.

Feeney began to also attract a national following in the 1930s with his move to New York and from a string of books and poetry that were being read not only by Catholics but also by the secular world. He was a highly sought-after lecturer and conversationalist and was referred to as the “American Chesterton.”

The priest was also heard by millions on the Sunday evening program The Catholic Hour and hobnobbed with celebrities and literary luminaries such as T.S. Eliot, Noel Coward, Fulton Sheen, Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy Thompson and Jacques Martain. Feeney, however, was no flatterer of the various high-profile people he associated with and, even at this stage of his career, sometimes belittled the most revered.

In 1936, while living in New York City, he was appointed to the prestigious post as editor of the Jesuit magazine America. While there, he made numerous converts, not only among the upper classes, but dock workers, janitors, waiters and cabdrivers—several of whom were Jewish.

THE ST. BENEDICT CENTER

Fr. Feeney returned to New England in 1940, the same year Catherine Goddard Clarke, who would later become a nun, and two other individuals established the St. Benedict Center. The original center opened in Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts and provided reading materials and, later, courses and lectures on Catholic subjects. It was approved and often praised by the local ecclesiastical authorities and it also received a blessing from Pope Pius XII. Over time, it expanded its operations and attracted followers worldwide.

Feeney was asked to join the staff and began giving talks and lectures. He was eventually assigned to the center full time. He kept up his priestly duties. This included performing baptisms and marriages, leading Mass, hearing confessions and making numerous converts.

At first, the success of the center was not a problem, as it still was supported by the local Church authorities, with some of the hierarchy attending Feeney’s talks. Over time, and with the increasing popularity of the center and the priest’s more pointed critiques of liberal Catholicism, concern grew not only at Harvard but Catholic schools, as well. Many students who came to the center complained about what was being taught, with parochial ones being just as bad off, as Sister Catherine Clarke surprisingly found out:

Our mistake at this time lay in our misconception of conditions in Catholic

colleges. We thought them much better than they were, and it took us two

years to learn how heavy were the inroads which Liberalism had made into

Catholic education. (2)

Ever since he had come to the center, Feeney had warned about the “evils in postwar secular education.” The priest received confirmation of this by speaking directly with students at the center.

“The students to whom [he] spoke were well aware of the truth of what he was

saying; indeed, they had complained to him many times of their

dissatisfaction and disappointment with their courses,” Clarke revealed in her

history of the center, originally published in 1950. (3)

A number of students courageously dropped out rather than continue to be indoctrinated. The decision came at a considerable personal cost since prestigious degrees from Harvard and the like pretty much guaranteed lucrative future employment opportunities. Yet, what shocked Clarke and other center members was that when these same students dropped out of the secular schools and decided to enroll in Catholic schools, they found little difference:

We were completely unprepared, therefore, for the return of these students who

transferred to Catholic colleges, bearing the same tale of disappointment and

dissatisfaction we had heard from them before. They had found not too much

difference between the college they had left and the college to which they had

transferred. (4)

Nothing distinguished a Catholic higher school of education from its secular counterpart. This shows that the liberal- ization of the Church and its schools was going on well before Vatican II in the 1960s:

For both colleges were similar in aim and in outlook, in presentation of material and in subject matter. The Catholic college, it is true, did not utter such explicit apostasy. Its apostasy was more implicit and took the form of a wholesale aping of secular standards. (5)

The conversions, his criticism of higher education (both Catholic and non-Catholic) and students prematurely leaving their studies all contributed to the eventual excommunication of Feeney. It came to a boiling point with the issuance of the Center’s newly founded magazine From the Housetops and an article by one of its contributors Dr. Fakhri Maluf, titled “Sentimental Theology.” (6)

While the courses and lectures by Feeney and the center’s staff were given verbally, Maluf’s piece was in black and white and therefore could not be easily dismissed. This gave Feeney’s opponents the opportunity to question his stance on the salvation doctrine. However, a closer look at the situation shows that he had been doing more than just expounding on extra ecclesiam nulla salus—he had been exposing and criticizing liberal Catholicism.

This is what so many contemporary traditional Catholics miss about Feeney. It was not the salvation doctrine by itself, but the entire Modernist program he saw unfolding before his eyes. Instead of praise for courageously speaking out against it at great personal cost, Feeney has been treated with contempt, both then and now.

In their campaign to silence him, however, his enemies concentrated on the salvation doctrine and, although there was never an official proclamation on the matter from the Vatican despite Feeney’s pleas, it was enough to divert attention away from his overall criticism of liberal Catholicism.

In the end, Feeney was excommunicated not for a doctrinal matter or because he held a heretical belief. Rather, he was excommunicated for his disobedience to superiors, which many view with skepticism.